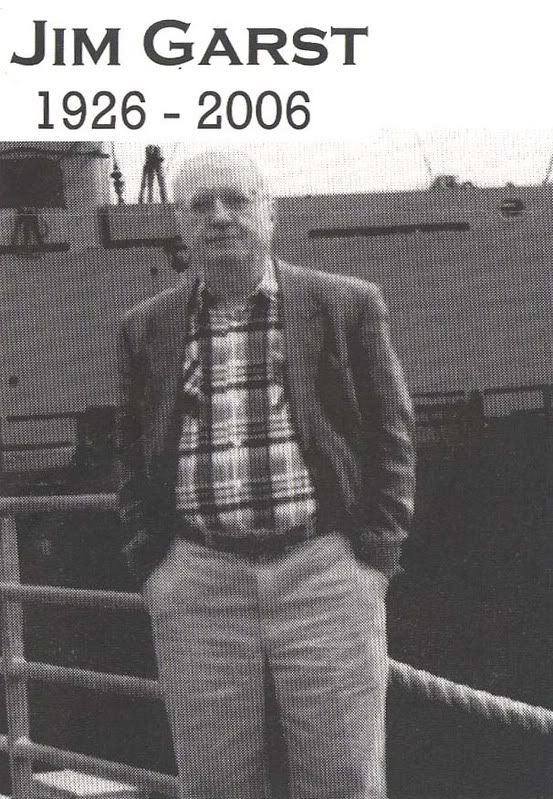

Jim Garst passed away on December 8th. He was the husband of my wife's cousin Rena:

GARST--James D. The Board of Directors and membership of the Mitchell-Lama Council mourn the passing of James D. Garst. He was a member of the Council's Board of Directors and its legislative representative for more than thirty years. He was a tireless and authoritative advocate for the cause of affordable housing. Murray Raphael President

GARST--James D. Beloved husband and best friend of Rina, died on December 8th at the age of 80. Jim's dedication to social justice showed in all his work. He retired as a lobbyist in Albany for Mitchell-Lama housing, tenant protection and neighborhood preservation. As a volunteer, he continued that fight and one for universal health care in the United States. A memorial will be announced at a later date. Donations in Jim's memory may be made to: New York State Tenants and Neighbors Coalition at 236 West 27th Street, NY, NY 10001 or to an organization of your choice which works for universal health care.

I googled Jim and found some interesting info. He was the editor of the UCLA Bruin back in 1949-50. It was the height of the McCarthy era and Jim was pretty pink. There was a great deal of campus strife. Frank Mankiewicz had been a previous editor and some guy who was to become pretty famous writer named Clancy Sigal was around. Most of the guys were older and more worldly, having served in WW2 and then gone to school on the GI Bill. From the history of the newspaper, written by George Garrigues:

"The Men's Lounge of Kerckhoff Hall was in the 1950s a world of massive leather chairs, pipe tobacco, polished wooden walls and noisy chess players. The balcony was a good place, in the early morning stillness, for a weary Daily Bruin night editor to sleep for a few hours before his 8 o'clock class, after he had driven the ASUCLA station wagon through darkened city streets from the print shop, in Hollywood, let himself in at the back door of Kerckhoff with his key and stumbled his way to the Men's Lounge without turning on any lights that a cruising campus cop might spot.

Occasionally the chess players were banished to another room as the Men's Lounge was subverted for use by the University's Board of Regents or, more often, by a standing-room-only meeting of the Student Executive Council considering some potent political issue. On the evening of Feb. 21, 1951, just such a crowd gathered in the Men's Lounge for an SEC meeting that had been moved from the smaller, third-floor Memorial Room. Most of the Bruin staff was there to watch a crucial vote taken on editorial appointments. Fraternity men and football players were there, too, to lobby for the Daily Bruin staff choices to go down in defeat.

At issue were two key appointments still vacant from the beginning of the semester three weeks before -- the editor-in-chief and the feature editor. In a larger sense, though, it was not a vote for or against any particular nominees but it was a vote for or against the Bruin's controversial policy of allowing all shades of political opinion on its feature page. Acting Editor Jerry Schlapik had written in that morning's Daily Bruin:

One by one the lights are going out all over this country of ours. Loyalty oaths have been all accepted, political groups have been all but outlawed, speakers and writers have been all but silenced.

The issue is not that of conservative versus liberal . . . The question before the nation is whether we shall continue to enjoy the luxury of free expression, and people of every political, economic and social belief are lining up on both sides.

One of those lights that may be going out now is the small, wavering flame of independence still flickering in the offices of The Daily Bruin. (DB, 2/21/51.)

Most of the older staffers present could look back over many another evening of sweating out the semiannual ritual of Student Executive Council's interviewing of and voting on the staff nominees for editorial positions. Editor Paul R. Simqu (fall 1947) later called the Council meetings "the bloodiest sensitivity training type sessions I had ever experienced. Grown men and women were reduced to tears at these affairs, and several changed universities when they didn't get what they wanted -- after being eviscerated by their peers in front of their peers." (Questionnaire.)

But one facet of the selection process had changed from Simqu's time -- the Bruin began reporting in detail as much of the Council meetings as it could -- which often was not much, because the usual practice was for the Council to go into closed session to interview the candidates and debate their qualifications. Up to 1949, detailed stories about Daily Bruin editorial appointments (or rejections) were rare indeed.

It was a tougher group of student editors who controlled the Bruin after 1949, and ranged against them was a tougher, more dedicated group of conservatives who attempted to do their duty to their country at war in Korea by cutting down on any controversial topics that might give aid and comfort to the enemy. The resulting clash made a loud noise that heated up the pages of the Bruin itself.

In 1949, the Bruin got its first admitted, honest to-God, card-carrying Communist staff member. Helen Edelman was a gift to the conservatives, who finally had an albatross they could hang around the neck of the liberal Bruin. Edelman, according to Editor Martin A. Brower (spring 1951), was "an emotional, fine, artistic person who won a scholarship to USC for her music ability . . . but who grew so disgusted with the administration at USC she joined the Communist Party . . ." (Questionnaire.)

And Editor Grover Heyler (spring 1949) remembers Edelman "mostly for a marvelous evening of Chopin that she delivered at my house when I entertained members of the staff. She was an accomplished pianist. I was told later she rose to the improbable position of social editor . . it seems very funny if true." (Questionnaire.) [It wasn't true. Her nomination was rejected by the Student Council.]

Edelman figured prominently in testimony by Dean of Students Milton Hahn before the state Senate Committee on Un-American Activities in 1957. Hahn said she exerted considerable influence upon the editorial policy of the Bruin and that she held an editorial board position although, as a matter of fact, she did neither.

It is more probable that the Daily Bruin exercised its sinister influence over Helen Edelman, just as it did over many another good student writer. The Bruin allowed her to become "an excellent writer and reporter [who] worked hard, and wrote stories without slanting," as Editor Brower put it.

"She may have joined the Bruin to infiltrate, but I think she found a liberal, interesting compatible group of people and merely enjoyed her association because she was accepted as what she was." (Questionnaire.)

At any event, Edelman's coverage of day-to-day news stories (she was assigned to the Student Executive Council for three semesters) was objective sometimes to the point of dullness; subjectivity was considered bad form by Bruin editors, no matter what the color of the writer's party card. Her feature-page articles, however, were written to the Communist viewpoint, unashamedly.

Editor Jack Weber (spring 1953) believes that Eugene Blank, a night editor who was rejected for feature editor at that Feb. 21 meeting, was also a Communist. (Questionnaire.) Weber offers no proof, and Blank's own words would seem to belie this assertion: "I like the American form of government very much, so much that I feel justified in being angry with a group of people who are riding rough shod over the principles upon which it is based." (DB, 2/21/51.) Without further evidence, the most that can be said of Blank is that he was a supporter of Henry Wallace's Progressive Party, as many Americans were in 1948.

The road to Feb. 21, 1951, began, perhaps, with the Eric Julber column calling Student Executive Council a "crew of red-baiters and stallers" (see Page 89). Although Julber was ousted by the editor for incorrect reporting and the possibility of "poor taste" (SEC, 4/23/48), the Student Council nevertheless voted to reprimand feature editor Jim Garst for allowing the article to be run.

The council defeated a motion to remove Garst, but four days later petitions were circulated on campus to oust him. (DB, 4/27/48.) Nothing came of them, and Garst was reappointed feature editor for the fall term 1948. Still, he had by this time become a controversial figure, and the controversy was made no less intense when a series of articles against Universal Military Training was run on the feature page. The series led Dean Hahn to suggest in a letter to Student Body President William Keene and Editor Charles Francis that the Bruin might be "liable to prosecution" because of them. (Chanc, 1948, Folder 40, 7/27/48.)

The failure of the recall movement against Garst, however, left the Bruin in a strengthened position. In January 1949, the staff presented to the Council a single slate for its approval "for the first time since before the war . . . No alternates will be offered." (DB, 1/15/49.) Editor Grover Heyler (who later became the Alumni Association representative on Student Legislative Council) believed the reason for the break in tradition was because of the "relatively conservative cast" of Bruin nominees: "myself, Dick Hill, Len F, none of us was very wild-eyed and I recall that members of the Council . . . seemed by their comments to indicate that the 'situation' was under control."

Pretty interesting! I never spent much time talking to Jim and I wish I had known that. For whatever reason I found it hard to engage him in conversation. Actually, I do know, but mentioning it would start an argument with the Mrs. So truth falls victim to prudence and respect for the departed (at least for now)

No comments:

Post a Comment