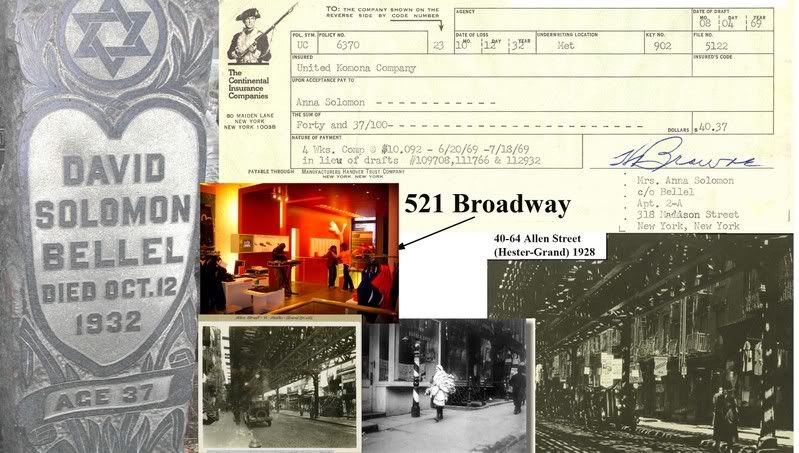

Columbus Day always had a special meaning to my father, it was the day his world came apart. Just like the character Sephardic Dave Karos, in "Dave At Night," by Newberry Award Honor Winner Gail Carson Levine (a Sephardim) he came home to find out his father had died in a fall. For Dave Karos, it was a fall from a scaffold. For my father it was an elevator collapse at 521 Broadway where he worked for United Kimono. I am thankful for Marcia Haddad Ikonomopoulos, the Museum Director of Kehila Kedosha Janina, for supplying me with the photo of my grandfather's grave (at Cypress Hills) and a Brotherhood of Janina membership listing from 1928 which supplied the forgotten Broadway factory address. In return I sent her some old Allen Street photos of that era (in the collage above). This is the area where many of the Romaniotes from Janina used to hang. 521 Broadway is now the home of the Puma store. The making of kimonos was considered part of the "white goods" manufactured in many of the sweatshops of New York. The girl in the picture avbove is carrying a stack of them. Also included in the collage is something my father had saved from his mother, a statement from the insurance money she received ($10 a week) from my grandfather's death.

Columbus Day always had a special meaning to my father, it was the day his world came apart. Just like the character Sephardic Dave Karos, in "Dave At Night," by Newberry Award Honor Winner Gail Carson Levine (a Sephardim) he came home to find out his father had died in a fall. For Dave Karos, it was a fall from a scaffold. For my father it was an elevator collapse at 521 Broadway where he worked for United Kimono. I am thankful for Marcia Haddad Ikonomopoulos, the Museum Director of Kehila Kedosha Janina, for supplying me with the photo of my grandfather's grave (at Cypress Hills) and a Brotherhood of Janina membership listing from 1928 which supplied the forgotten Broadway factory address. In return I sent her some old Allen Street photos of that era (in the collage above). This is the area where many of the Romaniotes from Janina used to hang. 521 Broadway is now the home of the Puma store. The making of kimonos was considered part of the "white goods" manufactured in many of the sweatshops of New York. The girl in the picture avbove is carrying a stack of them. Also included in the collage is something my father had saved from his mother, a statement from the insurance money she received ($10 a week) from my grandfather's death.From the book, "Rosie's Mom," the story of Rose Schneiderman, by Carrie Brown:

After the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the New York state legislature passed several new laws regarding factory safety, including a law limiting the work week to fifty-four hours for women in many factories.

The new law, however, was rarely enforced. In 1913, girls in candy factories still spent thirteen hours a day packing chocolates; in an ostrich feather shop seventeen-year-olds worked from early morning until 9 pm three nights a week. In the canneries, where the new law did not apply, women worked as long as 119 hours a week during the harvest season. And in 1913, youngsters in the white goods trade were still working 60 hours a week, in spite of the 54-hour law.

The white goods workers had watched the shirtwaist strike and they were encouraged. They watched the Triangle fire and they knew that their own shops, in rundown wooden tenement buildings and basement sweatshops, were even more dangerous. Finally, they began to listen to Rose Schneiderman. She came back, again handing out circulars in front of factory doors and climbing up onto her little ladder to speak. She asked them to come to meetings after work; she urged them to join the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Her work was matched by Fannia Cohn, another Jewish immigrant–-a middle class woman who had chosen life as a garment worker because of her commitment to the cause of workers. In her childhood in Poland, Cohn had absorbed a revolutionary fervor, and she passed it along to the young white goods workers as she taught them English and the principles of trade unionism at the same time.

No comments:

Post a Comment