September 15th-October 15th is Hispanic American Heritage Month. There was an excellent article in the Times' City Section this past Sunday on Dominican hopefuls playing for the Staten Island Yankees. Here it is: "Los Muchachos del Verano," By SAKI KNAFO, ON a clear June evening at the Richmond County Bank Ballpark in Staten Island, a young pitcher named Francisco Castillo jogged in from the bullpen, his boyish features set in a businesslike expression. It was the second game of the season, and his team, the Staten Island Yankees, was down two runs in the fourth inning. Mr. Castillo, a 19-year-old from the Dominican Republic who had arrived just four days before, had been summoned to prevent further damage. Watched by a crowd of about 6,500 — the largest he had ever pitched for — Mr. Castillo approached a ball lying on the mound, reached for it with his glove, missed and had to try again. If the fumble was the result of nerves, that would have been entirely understandable. Mr. Castillo, a Spanish-speaking kid wearing braces on his teeth, was making his debut on the team, which is an entry-level club in the New York Yankees’ system. An excellent season here would bolster his chances of climbing to a higher rung on the minor-league ladder — and maybe, someday, even to Yankee Stadium, the shrine to baseball in the Bronx. A lackluster season, an injury or an unfavorable assessment from a coach could land him back on the sandlots of Baní, the dirt-poor city in the Dominican Republic where he was born and raised.

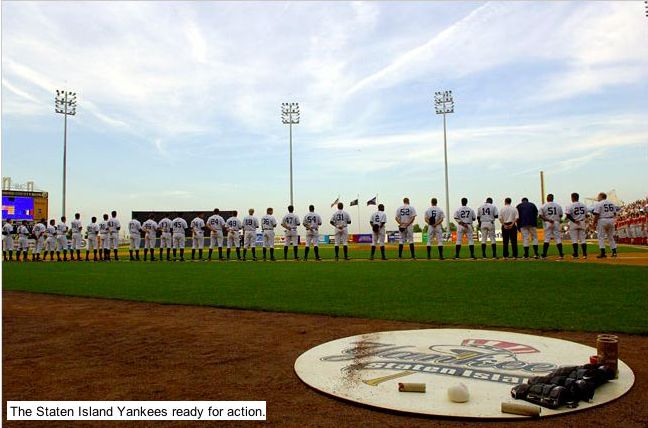

September 15th-October 15th is Hispanic American Heritage Month. There was an excellent article in the Times' City Section this past Sunday on Dominican hopefuls playing for the Staten Island Yankees. Here it is: "Los Muchachos del Verano," By SAKI KNAFO, ON a clear June evening at the Richmond County Bank Ballpark in Staten Island, a young pitcher named Francisco Castillo jogged in from the bullpen, his boyish features set in a businesslike expression. It was the second game of the season, and his team, the Staten Island Yankees, was down two runs in the fourth inning. Mr. Castillo, a 19-year-old from the Dominican Republic who had arrived just four days before, had been summoned to prevent further damage. Watched by a crowd of about 6,500 — the largest he had ever pitched for — Mr. Castillo approached a ball lying on the mound, reached for it with his glove, missed and had to try again. If the fumble was the result of nerves, that would have been entirely understandable. Mr. Castillo, a Spanish-speaking kid wearing braces on his teeth, was making his debut on the team, which is an entry-level club in the New York Yankees’ system. An excellent season here would bolster his chances of climbing to a higher rung on the minor-league ladder — and maybe, someday, even to Yankee Stadium, the shrine to baseball in the Bronx. A lackluster season, an injury or an unfavorable assessment from a coach could land him back on the sandlots of Baní, the dirt-poor city in the Dominican Republic where he was born and raised.Behind him as he pitched in that game in June, the Manhattan skyline, visible across New York Harbor, shimmered in the fading sunlight beyond the outfield fence. The potential distractions were limitless.

But at this moment on the mound in Staten Island, Mr. Castillo had a job that commanded his full attention. The first batter for his team’s opponents, the Brooklyn Cyclones, popped out. Mr. Castillo struck out the second on three pitches. The next man up blasted a fastball off the left-field wall for a double. Mr. Castillo took a deep breath and, on the second pitch of the next at-bat, coaxed a fly ball to center for the final out.

Trotting back to the dugout as the crowd showered him with applause, the young man crossed himself and glanced heavenward.

“It’s like walking in the desert,” Mr. Castillo, speaking through an interpreter, said later of the experience of playing before thousands of fans. “You can barely walk. But if there are others with you, urging you on, ‘Walk! Walk!’ well, you’re going to try to walk faster.”

Mr. Castillo was among four Dominican players assigned to the roster of the Staten Island Yankees at the beginning of the season. Another was his friend Toni Lara, a lithe, fine-featured 22-year-old who had known the man he called “hermanito” — “little brother” — back in Baní. The two met five years earlier at a baseball academy; as with most major-league prospects in the Dominican Republic, baseball was a substitute for high school.

Of the thousands of aspiring young ballplayers in their impoverished country, they were among the few who stood out enough in the Yankee training complex in the Dominican Republic to be flown to New York, put up in student apartments and paid about $1,000 a month to play the game they adore.

Over the last generation or two, the business of baseball has been transformed by the emergence of Latin America, and especially the Dominican Republic, as a source of plentiful, cheap and talented labor. Dominican players often command perhaps $30,000 in signing bonuses, about half as much as Americans, and many sign when they are 16, a few years earlier than most of their American counterparts. This year, the Yankees supplied their Staten Island affiliate with five Venezuelan players in addition to the four Dominicans, roughly twice the average Latin American contingent of seasons past.

Wherever players were born, their chances of success remain dauntingly slim. At least 95 percent of minor-leaguers never advance to the majors.

‘The Ballpark Is Our Date’

On June 17, Mr. Castillo and his fellow Dominicans landed at Newark Liberty International Airport, a world away from the dusty fields of their hometown. Mr. Castillo clutched a teddy bear, a gift from his mother, as the team bus shuttled the group through the industrial wasteland of northern New Jersey.

Their first stop was the Staten Island stadium, in the St. George neighborhood. Although it was 10 p.m. and the players hadn’t yet unpacked, they were led out onto the darkened field. Across the water, the Empire State Building blinked its welcome.

At first, none of the players seemed to notice the skyline; standing near the dugout, they marveled instead at the size of the stands, capacity 7,171.

Then Mr. Castillo, wearing one of his new team’s gray caps, wandered away from the pack and stepped onto the infield grass. “Is that New York?” he asked in English, gazing wide-eyed at the distant lights, with the air of someone who had happened upon a pretty flower. Then he pulled out his new camera and snapped a couple of pictures.

The athletes, particularly the Latin American players, worked even harder than their hectic schedule demanded. On their rare days off, the players seldom strayed from Grymes Hill, a leafy neighborhood in Staten Island where they had unadorned Wagner College apartments, sleeping two to a room like students or, for that matter, migrant laborers.

On days when the team was not on the road, the players were up at 11 a.m., to shower and dress and check in at the stadium by 1:30. Lunch for the Dominicans was typically rice and beans, maybe chicken and plantains, at El Famoso Comida Latina, a nearby restaurant. Then they would head back to the stadium for exercise, drills and finally the game. After showering, changing, grabbing a meal and fielding questions from the local press, it was back to the apartment, and maybe some ESPN on television before bed a little past midnight.

Some of the Americans on the team socialized in local bars and wandered around Canal Street or Times Square on their off days. But Mr. Castillo and the other Dominicans, who all roomed together in a sparsely furnished apartment lacking even a stand for the television set, focused on their work even during downtime.

“The ballpark,” Mr. Castillo said in the stadium parking lot after a game, “is our date.”

Still, the players did not live in isolation. Rather, they immersed themselves in an alien environment, and they adapted to life in America in divergent ways.

While Mr. Lara, for example, did not know enough English to feel comfortable bantering with his American teammates, Mr. Castillo practiced his English whenever possible, tossing off phrases like “chillin’ like a villain.” He spent his spare time poring over Christian self-help books in both English and Spanish, and he diligently recorded his private thoughts in a diary in which the entries were written in the form of letters to God.

Those differences were on display the afternoon that the Latino players headed off to buy lunch at a nearby deli. Mr. Castillo breezed into the store and zeroed in on a package of corn muffins, a close cousin of the popular Dominican dish pan de maiz. Mr. Lara, meanwhile, shied away from asking a clerk to recommend what kind of phone card to buy, turning instead to a teammate for help — though the teammate’s command of English didn’t go much beyond knowing the choruses of a few hip-hop songs.

The Tribulations of Toni Lara

At 22, Mr. Lara was almost too old to be a member of the Staten Island Yankees. Most of his contemporaries had already climbed higher on the minor-league ladder, or tumbled off it. This was Mr. Lara’s second season pitching on Staten Island; last year, he switched from starting games in the regular rotation to pitching in relief whenever needed.

“I won’t lie to you,” he said after his first game this summer. “I was throwing too many balls. So I thought I was going to have a bad year. But then I asked to be a reliever, and I had a great season.”

This season, however, he was struggling. In the eighth inning of Mr. Castillo’s first game, Mr. Lara came on in relief while his friend watched from the dugout. On only his second pitch of the season, Mr. Lara surrendered a shot over the right-field wall for a three-run home run. Mr. Castillo hammered his fist in frustration.

After that miserable outing, Mr. Lara sat crouched outside the clubhouse beneath a sign emblazoned with the words “Assume nothing.” “Great welcome,” he said ruefully, his grim expression easing into a smile. “But, hey, press on. That’s what happens to pitchers.”

His second appearance didn’t go much better: he gave up two runs and walked three batters in two and a third innings. In his third game, against Hudson Valley, Mr. Lara seemed to find his groove, going the same distance without allowing a hit. Still, nine games passed before he got another opportunity to pitch.

While Mr. Lara languished on the sidelines, his friend, Mr. Castillo, was pitching well, winning a spot in the rotation. On July 9, Mr. Castillo turned in one of his finest performances of the season, with five scoreless innings against the Vermont Lake Monsters.

The next afternoon, while the players were changing in the clubhouse, Mr. Lara was summoned to the front office. When he returned a half-hour later, he was crying. After four years in the Yankee organization, he had been released. Under the terms of his work visa he was required to leave the United States immediately. The Yankees would send a cab to his apartment in Grymes Hill the next day to drive him to the airport so he could catch a flight back to the Dominican Republic.

The Lesson of the iPod

As the community relations director for the Staten Island Yankees, Polo Burgos spends lots of time speaking at local events and racing around the field with local kids. As the only Dominican in the front office, he also serves as what he describes as a nanny for the Latino players, helping them shop and cash their paychecks, and occasionally haranguing them about the importance of learning English and saving money.

On the afternoon Mr. Lara was released, Mr. Burgos and several players were wandering through the aisles of a large electronics store in a strip mall off Richmond Avenue on Staten Island. For Mr. Castillo, the shopping trip was the first time he had traveled around town beyond the immediate vicinity of the stadium. In keeping with the Yankees dress code, he wore a neat gray shirt with a collar, his sunglasses hanging from his neck. A glittering Movado watch on his strong wrist seemed to announce his aspirations.

Addressing a saleswoman as “corazon” (“sweetheart”), Mr. Castillo pointed to the latest iPod model and asked her the price in Spanish. Mr. Burgos quickly took over the exchange in English. “If they buy three, what kind of deal are they going to give them?” he asked.

Mr. Burgos haggled with the saleswoman for a good five minutes, his demeanor shifting from flirtatious to pleading to demanding. Then he turned back to his players and said in Spanish, “I’m not going to let you buy them here when you can go somewhere else and buy them for at least $15 off.”

Later, in the parking lot, Mr. Burgos launched into a lecture on fiscal responsibility.

“You! You!” he shouted over a flurry of snickers as the players made their way back to the car. “Hold onto your money. Don’t throw it away like that. These gadgets cost $300. You can buy a normal radio, you can buy a CD player for $15 each.

“Listen,” he went on. “Look at what happened with Lara.”

It was the first time all afternoon that anyone had mentioned Mr. Lara’s name. The laughter stopped abruptly.

As it turned out, Mr. Lara was not to complete the journey that had been marked out for him. The next day, when the cab came to take him to the airport, he and his belongings were nowhere to be found.

A week later, Mr. Castillo spoke about his friend’s disappearance, which had occurred the evening before his scheduled departure. “We didn’t have food for the night,” Mr. Castillo said. “So we went out to get some, and he stayed back watching TV. When we returned, he was gone.”

Mr. Castillo, along with the other players and Yankee officials, said that they had heard nothing from Mr. Lara, and no family members were located.

But such disappearances are far from rare. “Nobody wants to go back,” Mr. Burgos said. “Nobody. I got my citizenship years ago, because if someone told me I had to go back, I don’t know what I‘d do.”

To the Shrine in the Bronx

As of Friday, the Staten Island Yankees were in first place in their division. Mr. Castillo ranked 14th in the league in strikeouts, with 51. It looks as if he may spend next summer in Charleston, S.C., playing for the RiverDogs, a team on the next higher level of the Yankee organization.

In his time in New York, Mr. Castillo has not seen much of the city beyond the Spanish restaurant in St. George, the Staten Island Mall and some grocery stores. But one Monday in July he did get to visit that stadium in the Bronx.

Accompanied by a chaperon, team members took the ferry to Manhattan, then the No. 4 train to the Bronx. Emerging at 161st Street, they walked to Yankee Stadium, where they were met by a team official and spirited away on a guided tour of the field, the dugout, the team’s hallowed Monument Park beyond the outfield and, most amazing to them, the clubhouse.

The walls were lined with spacious wooden cubbies brimming with uniforms and bats, and boasting an array of awe-inspiring nameplates: Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, Mariano Rivera. A crowd-control barrier confined the minor-league players to the front of the room (major-league rules, the guide said), but it didn’t stop them from gazing around in hushed wonder.

Mr. Castillo’s first words were in English. “Oh, my God!” he said quietly. Then he pulled out his camera and took pictures.

Here's a slide show I created with images from the article's photo essay and images that espn had done on baseball in the Dominican Republic

1 comment:

Beautiful article. You should expand it in to a book. You've got a gifdt for conveying the inside story with subtlety and flare.

Post a Comment