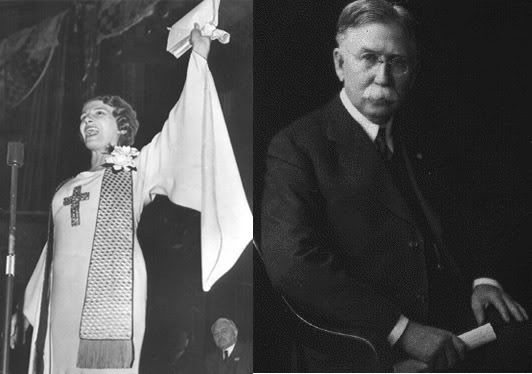

That's Aimee Semple McPherson and Edward L. Doheny in the picture. I found someone who has explained my reservations about There Will Be Blood in a way that I was unable to.

That's Aimee Semple McPherson and Edward L. Doheny in the picture. I found someone who has explained my reservations about There Will Be Blood in a way that I was unable to. What's Wrong With There Will Be Blood A blown chance to say something big about money and power in America By Timothy Noah

I half-agree with the near-unanimous praise for There Will Be Blood, Paul Thomas Anderson's loose adaptation of Upton Sinclair's Oil! The headline accompanying my Slate colleague Dana Stevens' review calls the film a "masterpiece." I would call it a halfterpiece. The first half of There Will Be Blood, and especially the film's dialogue-free first 20 minutes, ranks among the most thrilling moments I've witnessed on film. About midway, though, I felt that There Will Be Blood lost its clarity, for reasons that say something about the impoverished state of political discussion in the movies generally.

I haven't read Sinclair's 1927 novel, but I gather (from this Web site and others) that Anderson took from it the story of a California oil wildcatter, his son (who serves as the book's narrator), and a Holy Roller minister (who in the book is a bit more obviously a fraud and, apart from his sex, is modeled on Aimee Semple McPherson). What Anderson left out of There Will Be Blood was the son's development as a socialist in reaction against his father's corrupt capitalism. In the film, the wildcatter acquires drilling land through deception and cheats the minister out of $5,000, but in the book, he is also a systematic dispenser of bribes to politicians. Sinclair based his wildcatter on Edward L. Doheny, a fantastically successful oil tycoon in Los Angeles (Doheny Drive in West L.A. is named for him) who was disgraced in old age by the Teapot Dome scandal. Doheny, along with Sinclair Oil founder Harry Sinclair (no relation to Upton), paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to President Warren G. Harding's interior secretary, Albert Fall, in order to secure drilling rights on federal lands. Fall and Harry Sinclair went to prison, but with a team of high-priced lawyers Doheny somehow beat the rap. The Teapot Dome scandal, which first surfaced in 1922, is apparently what inspired Upton Sinclair, himself an active socialist, to write Oil!, and a fictionalized version of the scandal figures prominently in the narrative. Teapot Dome plays no role at all in There Will Be Blood.

Anderson acknowledges the Doheny link by making his wildcatter (who in the film bears the deliciously ironic name Daniel Plainview) a native of Fond du Lac, Wis., which was Doheny's hometown. Like Sinclair's fictionalized Doheny (whom Sinclair calls Joe Ross), Plainview is mostly admirable at the start of the narrative, as he builds up his oil empire, and mostly corrupt at the end. But Plainview's corruption is less well-defined than Ross'. Ross has yielded to capitalist imperatives and eventually gives up his company's independence to join a corrupt syndicate. Plainview, on the other hand, is aloof both personally and in his business (his refusal to sell out to Standard Oil is portrayed mainly as a manifestation of his mental instability); his evil is innate. The moment There Will Be Blood began to lose me can be found on Page 73 of the shooting script. "I have a competition in me," Plainview tells a man he thinks is his brother.

I want no one else to succeed. I hate most people. … I've worked people over and gotten what I want from them and it makes me sick. Because I see that all people are lazy. They're easy to take. I want to make enough money that I can move far away from everyone.

It's no small credit to Daniel Day-Lewis' extraordinary acting performance that he's able to make even these mustache-twirling lines halfway convincing. But the scene is a sign of desperation on Anderson's part. From this point in the film on, his subject ceases to be the acquisition of money and power in America and starts being the madness and cruelty of Daniel Plainview. For all I know, this shift from the physical to a psychological landscape makes Plainview a richer character than Sinclair's Joe Ross. (To repeat: I haven't read the novel.) To my mind, though, what's extraordinary about There Will Be Blood isn't the film's characters at all; it's the painstaking way Anderson lays out how the oil business works and how Plainview gets rich in it. The viewer anticipates that grand political themes will play out, but these never come to fruition.

I can understand why Anderson wouldn't necessarily want to adopt Sinclair's leftism or any sort of didacticism. It's a movie, after all, not a political tract. But in the past, movies from Intolerance to It's a Wonderful Life to Chinatown have routinely been built around the question: How does the world we live in work? The filmmaker's stance could be that of a despairing (if somewhat hypocritical) prophet, like D.W. Griffith's, or cornball-hopeful, like Frank Capra's, or darkly nihilistic, like Roman Polanski's and Robert Towne's. But one left the theater feeling that some idea about the larger society the film's characters inhabit was being set forth. In There Will Be Blood, by contrast, a promisingly broad canvas shrinks. Anderson has a little to say about the conflict between God and Mammon—his film's title is derived from Exodus 7:19 (though not the King James version, which states, less dramatically, "there may be blood")—but since the minister, Eli Sunday, and Plainview are both compromised figures, their mutual hatred carries little thematic weight. Also, Anderson never shows how Sunday becomes the big-time minister he's evolved into at the end of the movie, so the "God" end of this smackdown lacks heft.

Anderson's failure to say anything interesting or even coherent about the structure of American society is not unusual. I can't remember the last time I saw an American movie that did (excepting documentaries; gangster movies, which inherited this function from The Godfather; and the occasional movie promoting ethnic, sexual, religious, or some other form of tolerance and inclusiveness). Consider Lions for Lambs, one of the many 9/11-inspired movies that flopped recently. As Slate's Stevens pointed out in her review, that film promoted, in a lame be-true-to-your-school sort of way, greater civic involvement. But when the idealistic professor played by Robert Redford was asked by his frat-boy screw-up student why he should bother to engage when all efforts were bound to fail, professor Redford mysteriously declined to respond as any real-world political activist would, i.e, "Sometimes people like us can make a meaningful difference." Instead, he coughed up, "At least you can say you did something."

Time to film Middlemarch, shifting the locale to modern-day Cleveland?

1 comment:

To create a story about a man than complex not only the writing and the acting deserves a bit more respect than pseudo intellectualism. He took some very serious jabs and big business. People know corporations are corrupt and beating them over the head won't change it because they are the problem, lazy cattle being herded. Don't stick up too much for the common man I am one of them and many are not worth defending either.

Post a Comment